Barbara McClintock (June 16, 1902 – September 2, 1992) is a famous American geneticist. Certainly one of the brightest in the 20th century.

by Lucie NIETO

Barbara McClintock

Barbara McClintock, a tomboy

Born under the name of Éléonore, her parents renamed her Barbara 4 months later, considering that this first name corresponds better to the temperament of the child. She grew up in Hartford, Connecticut. She is the third of the four children of doctor Thomas Henry McClintock and Sara Handy McClintock. His parents moved a few years later to Brooklyn, New York. Unlike girls of her age, Barbara plays baseball, enjoy boxing or ice skating. It’s hard to make friends when you don’t like girls’ games, and when boys prefer to play with boys.

Barbara soon became interested in science and wanted to continue her studies at Cornell University, a very prestigious university. Her mother dislikes this idea because, according to her, an overeducated girl will not find a husband.

Besides, university studies are very expensive. Returning from the war (WWI), her father defended her daughter and she entered the faculty of agronomy at Cornell in 1919 at the age of 17. A self-confident woman who goes with her ideas, what does it matter if people appreciate or not.

The only woman to obtain her diploma in botany

At Cornell University, she studied botany and graduated in science four years later, in 1923. Her passion for genetics came from a course taught by CB Hutchinson, a geneticist, and professor at the University of Harvard. Following Barbara’s interest, Hutchinson offered her to attend at his genetic course at Cornell in 1922, an invitation she accepted with pleasure.

At the time, Nettie Stevens had already shown that physical characteristics (skin colors, eyes …) are transmitted from parents to their offsprings through chromosomes. Since then, research in genetics has accelerated. And Barbara is passionate about this fashionable subject.

Maize, a fascinating subject ?

Barbara is not the kind of woman to be distracted by boy’s invitations to enjoy a pack of popcorn in the theater. Freshly graduated from Cornell, she wants to continue her research. She is dedicated to studying the genes of corn to understand how grain colors are passed from one generation to the next.

She works like hell, studying the corn cells under a microscope. Reviewing different species of yellow, white, brown, or purple corn. She studies, in particular, the chromosomes of corn, with her friends Harriet Creighton, American botanist and geneticist, and Georges Wells Beadle, an American scientist who was awarded the 1958 Nobel Prize.

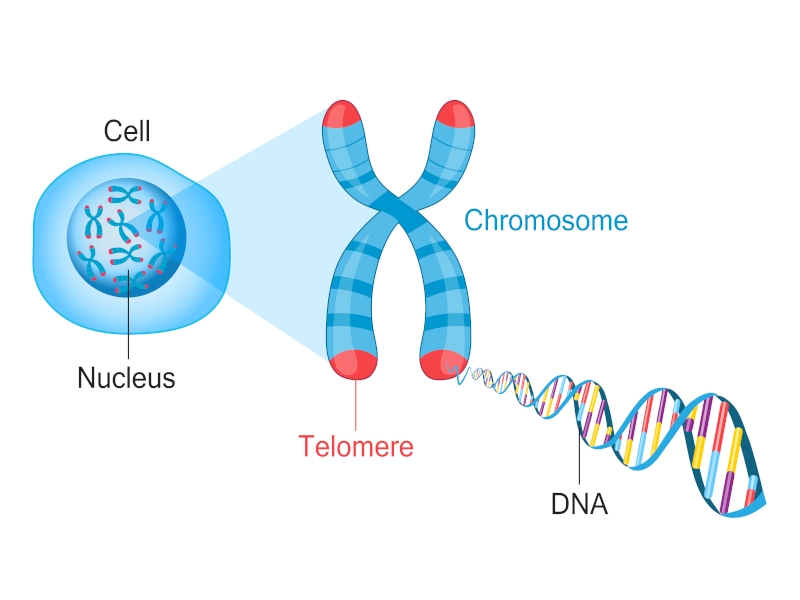

To understand her work, it must be understood that our appearance and functioning is defined by our DNA. Size, color, shape, digestion … the precise recipe is included in our DNA and it is located in each cell, grouped into chromosomes. Each piece of the chromosome has a specific role.

Barbara knows exactly where the piece of chromosome that defines the color of the kernels is. It was thought at the time that if there was a change, it was linked to a mutation.

Through her experiences, Barbara demonstrates that colored spots appear and disappear on her corn seeds from generation to generation. Which is amazing. To understand why parent corn produces fruits of different colors, she understands that pieces of genes “jump” from one chromosome to another, causing a change in the color of the grain. A revolution at the time, but few people took it seriously.

Some colleagues jaleous of her talent.

Despite a growing reputation at Cornell, she must leave. The faculty decrees that they will never offer a permanent position to a woman. She doesn’t give up on her dreams. She lives on small research grants entrusted to her here and there, sleeping very little to carry out her research. Her work ends up paying. She is allowed to join Caltech where she will be the first woman to carry out postdoctoral research. Then she was hired at the University of Missouri. She is 34 years old.

But then again, this is a big disappointment. She has to teach, but her students are terrified of her temper. Her colleagues envy her talent and she is excluded from all Faculty councils. Disgusted, she left the University of Missouri to join the laboratories of Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island. She states:

“If you know you are on the right track, if you have this inner knowledge, then nobody can turn you off… no matter what they say.”

Extensive research and a Nobel Prize as a reward

Freed from her teaching duties, she is free to work with geneticists and even plant corn for her research. She makes many discoveries that are not taken seriously by her peers. Too bad, because in the years that will follow other researchers will prove that she was right.

In the 60s, she accumulated scientific prizes. And at the age of 81, she learned on the radio that she won the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology.

Barbara McClintock

16th June 1902

2nd September 1992